The production of health presents a central concern to the health economist and to public policy. Consider

that the role of health care in society, including medical care provided by physicians, is ultimately a production

question. We must learn about the determinants of health and about the contribution of health

care. We can then better understand what decisions, both personal and public, will best produce health.

In medical terminology, this chapter addresses the efficacy and effectiveness of all those features of life,

not only medical care, that plausibly contribute to our health. Unlike the typical doctor in practice, however, we

look for evidence of the response of a “treatment” in the change in the health status of populations, as opposed

to the treatment response of a medicine for the individual patient. We will see that the two approaches must remain

in harmony and that both are fundamentally searches for causal relationships.

THE PRODUCTION FUNCTION OF HEALTH

A production function summarizes the relationship between inputs and outputs. The study of the production of

health function requires that we inquire about the relationship between health inputs and health. The answers

that economists and medical historians offer to this question surprise many people. First, the contribution of

practitioner-provided health care to the historical downward trends in population mortality rates was probably

negligible at least until well into the twentieth century. Second, while the total contribution of health care is substantial

in the modern day, its marginal contribution in some cases is small.

This distinction between total and marginal contributions is crucial to understanding these issues. To illustrate

this distinction, consider Figure 5-1A, which exhibits a theoretical health status production function for the

population. Set aside the difficulties of measuring health status in populations, and assume that we have defined

an adequate health status (HS) measure. Health status here is an increasing function of health care. Also, to avoid a perspective that is too narrowly focused on health care, we specify further that health status

depends at least upon the population’s biological endowment, environment, and lifestyle.1 Thus,

HS = HS (Health Care, Lifestyle, Environment, Human Biology). Improvements in any of these

latter three factors will shift the curve upward.

A production function describes the relationship of flows of inputs and flows of outputs over a

specified time period, so the inputs and output in Figure 5-1A are measured over an implied period,

such as a year. In practice, we might use the number of healthy days experienced by the population

per capita, mortality rates, or disability days, to indicate health status.

To simplify the depiction, we have reduced all health care inputs into one scale called Health

Care. In reality, health care consists of many health care inputs. Some of them include medical care

provided by doctors of medicine or osteopathy, but other health care professionals also provide care.

Conceptually, the health care measure, HC, may be thought of as an aggregate of all these types of

health care, the aggregation being based on dollar values.

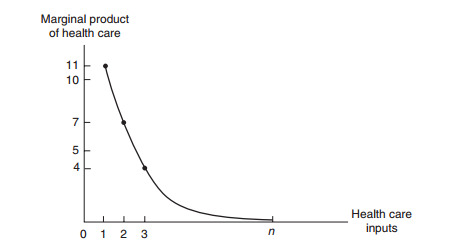

The marginal contribution of health care is its marginal product, meaning the increment to

health caused by one extra unit of Health Care, holding all other inputs constant. Increasing Health

Care from zero to one unit in Figure 5-1A improves health status by ΔHS1, the first unit’s marginal

product. Numerically, this first unit of Health Care has increased the health status index from 32 to

43; ΔHS1 = 11 Health Status units. The next unit of medical care delivers a marginal product of

ΔHS2 = 7, and so on.

These marginal products are diminishing in size, illustrating the law of diminishing marginal

returns. If society employs a total of n units of Health Care, then the total contribution of Health

Care is the sum of the marginal products of each of the n units. This total contribution as shown, AB,

may be substantial. However, the marginal product of the nth unit of medical care is ΔHSn, and it is

small. In fact, we are nearly on the “flat of the curve.” Marginal product is graphed on Figure 5-1B.

We have drawn the health production function as a rising curve that flattens out at higher levels

of health care but never bends downward. Would the health production function eventually bend

downward? Is it possible to get too much health care so that the health of the population is harmed?

This is a logical possibility under at least two scenarios. Iatrogenic (meaning provider-caused) disease

is an inevitable by-product of many medical interventions. For example, each surgery has its

risks. Combinations of drugs may have unforeseen and adverse interactions. If the rate of iatrogenic

disease does not fall while diminishing returns sets in, it is possible for the balance of help and harm

from health care to be a net harm.

Medical scientists, such as Cochrane (1972), have pressed the case that much medical care as

often practiced has only weak scientific basis, making iatrogenesis a real probability. Writing for the

public audience, Dubos (1960) and Illich (1976) once warned of a medical “nemesis” taking away

our abilities to face the natural hardships of life by “medicalizing” these problems. Illich argued that

this medicalization would lead to less personal effort to preserve health and less personal determination

to persevere; the result becomes a decline in the health of the population and thus a negative

marginal product for medical care.2

Return to the distinction between total product and marginal product. Often, the marginals,

rather than the totals, are relevant to policy propositions. For example, no one seriously recommends

that society eliminate all health care spending. However, it is reasonable to ask whether

society would be better off if it could reduce health care expenditures by $1 billion and invest those

funds in another productive use, such as housing, education,

transportation, defense, or other

consumption. We could even reasonably ask if health itself could be improved by transferring the

marginal $1 billion to environmental or lifestyle improvements.

Many of our government programs encourage health care use in certain population groups, such

as the poor and elderly. Other programs, such as tax preferences for health insurance, provide benefits

for those who are neither poor nor elderly and encourage their consumption of health care. The theoretical

issues raised here suggest that we question the wisdom of each of our programs. The theoretical

questions can be investigated with data of several kinds either directly or indirectly relevant to the

production of health issue. We begin with the historical role of medicine, which indirectly bears on the

issue of health production. After providing an overview of these efforts, largely the work of medical

and economic historians, we then turn to econometric studies of the modern-day production function.

Health Care and Health Insurance

health care | united health care | home health care | jobs health care | health care insurance | health care dental | Insurance and Substitutability

Health Care Spending in Other Countries

Examining the health economies of other countries enhances our understanding of the U.S. health

economy. Many countries have large health care sectors and face the same major issues. Table 1-1

shows how health care spending as a share of GDP grew rapidly in most countries between 1960

and 1980. A more mixed picture emerges after 1980. The health care share in the United States

continued to grow in each period after 1980 shown in Table 1-1, but growth was more modest in

most other countries.

The data also indicate the relative size of the U.S. health economy compared to that of other

countries. For example, health care’s share of GDP in the United States is nearly twice as large as

the share in the United Kingdom—a country with national health insurance. Is care costlier in the

United States? Is it higher quality care, or are we simply consuming more?

a 2009 or most recent year. OECD data for the United States may differ slightly from values reported by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Health Care Data, June 2011.

a 2009 or most recent year. OECD data for the United States may differ slightly from values reported by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Health Care Data, June 2011.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)